by Grace Gámez, Ph.D. |

Earlier this month, I traveled to Montgomery, Alabama, to attend the 2019 FreeHer conference – a gathering of system-involved women organized and hosted by The National Council of Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls. The conference was kicked off with a visit to the Equal Justice Initiative’s (EJI) Legacy Museum, built on the site of a former warehouse that held Black people who were enslaved.

The Legacy Museum is situated in downtown Montgomery and stands in stark contrast to the modern marketing and consumer culture of the current Alley Entertainment District. Though the genocide of the indigenous Alibamu people and the enslavement of African people will forever haunt the area, capitalism has built a bustling hipster economy of craft beers and popular food chains in the district.

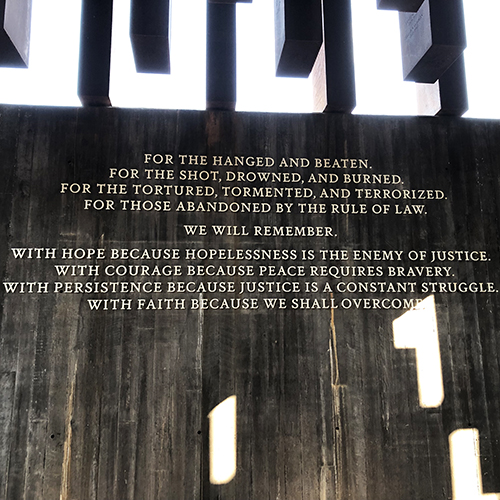

Such deliberate erasure makes the EJI museum and monument that much more radical.

- Photo by Grace Gámez | The EJI Legacy Museum is a radical monument to the indigenous Alibamu people and enslaved Africans.

- Photo by Grace Gámez | The FreeHer conference brought together system-involved women from around the country working to build safe communities for us all.

- Photo by Grace Gámez | FreeHer organizers were intentional about situating the conference within the context and conversation of slavery in America.

Just a short walk down from the Alley flows the sleepy Alabama River. Though the import of human bodies was banned by Congress in 1808, the domestic slave trade continued unabated and flourished. Between 1808 and 1860, the enslaved population of Alabama grew from less than 40,000 to more than 435,000. Alabama had one of the largest slave populations in America at the start of the Civil War. Each day in the 19th century, hundreds of enslaved people arrived at the riverfront and were paraded in chains down Commerce Street to be sold in the city’s slave markets. This tired, old river made Montgomery a principle slave-trading center.

The system will not abdicate power; it will not free us.

FreeHer organizers were intentional about situating the conference within the context and conversation of slavery in America because we see its roots within America’s punishment system. Just as slavery was dependent upon and maintained by the bodies of women and their children, so is incarceration, in all of its manifestations.*

There were several pieces of policy and practice that were highlighted over the course of the FreeHer conference that uniquely impact women and girls. These included the Adoption and Safe Families Act, felony murder statutes, mandatory reporters, and the foster-care-to-prison pipeline. There is important work to be done as it relates to reforming law and policy. However, we must be cautious that what we pursue does not expand the reach and power of the state and that we simultaneously emphasize the system’s inability to solve the crises it creates.

What was affirmed for me at session after session of the FreeHer conference is that to neutralize and unmake this well-fed, multi-headed hydra, diverse approaches are required. Yes, legislation and policy reform are imperatives. But reform cannot be the end goal. We cannot look to this modern iteration of white supremacist, nation-building to liberate and restore our communities.

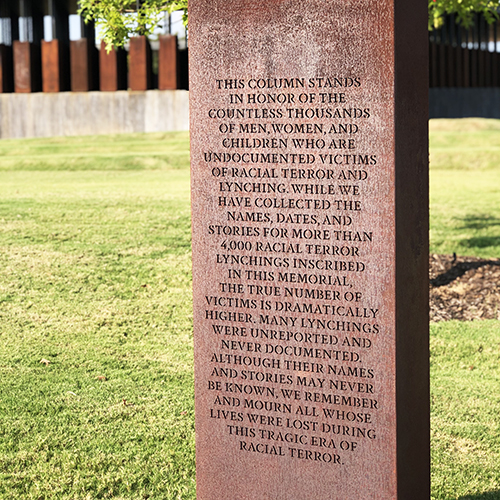

We have not attended to the barbarism that is America. The cancer of racial terror and bigotry has metastasized; we are sick with it. Slavery – albeit not the public, naked inhumanity of chattel slavery – is unbroken in America.

However, if we work to create conditions that make possible full and nourished lives for Black, indigenous, trans, differently-abled, differently-statused, women and girls of color, then everyone has a chance at not simply surviving, but thriving. And that is something we do for one another.

The system will not abdicate power; it will not free us. It is our deep investment in one another and in our communities that will get us free.

Dr. Gámez is the program director of AFSC-Arizona’s ReFraming Justice Project.

* English common law held a child’s basic legal status followed the father. If your father was free, you were free. However, in the 1660s, “special exceptions” were made. Children born to enslaved women, regardless of their father’s free status or white citizenship/subjecthood, inherited their mother’s unfree status, thus guaranteeing lifelong enslavement and generational slavery.

Categories: Blog, Reframing Justice, Uncategorized, Vision of Justice